What is the Sabbath For?

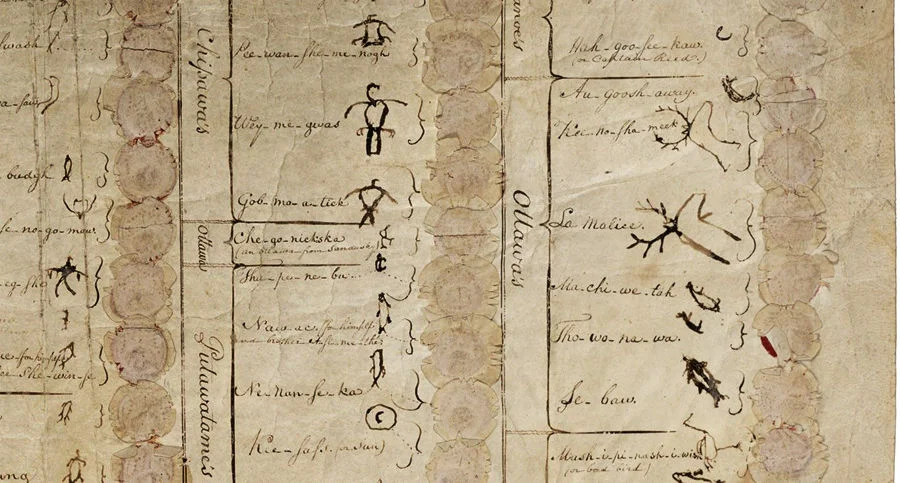

The Greenville Treaty of 1795. The Tribal Chiefs of the Wyandot, Lenape, Shawnee, Ottawa, Miami, Chippewa, Potawatomi and Kaskaskia nations signed the Treaty of Greenville using icons of animals as their signatures.

WHAT IS THE GOSPEL FOR?

August 25, 2019

Pentecost 11C

Luke 13: 10–17

Zion United Church of Christ

Tremont, Cleveland, OH

The world is not as God intends. The truth at the heart of the gospel is that God has empowered us to change that. This is what the Sabbath is all about.

Sermon notes are available online at Medium.

They can also be downloaded here in either pdf or eboook format.

What is the Gospel?

I have the greatest job in the world. Since taking my position three months ago, I have traveled all over the northeast region of Ohio. Each Sunday I have been visiting different congregations throughout the Living Water Association, sharing what I think to be a compelling vision. Today, I’m sharing with Zion UCC, a historic congregation in Tremont, Cleveland. Like I am today, I have been inviting people to be a part of something that I hope will truly change our communities. At each church, each and every Sunday, I’ve been asking people the same simple question, “What is the gospel?” So, I want to begin the same way with you this morning. Please turn to your neighbor or jot down a quick note to yourself the following question. If you were asked to explain what the gospel is, what would you say? What is the gospel?

I am here this morning to share the gospel with you. The gospel, as I have come to see it, is a mighty and dangerous story. It is the story of all stories; the story of stories, you might say. The gospel is the story of the yearning at the heart of the universe. It is the cry at the core of creation. It is a mighty story because it is about the force that brought Creation into being. It is a dangerous story because it threatens to unsettle us and rework us; it is the force that works to turn God’s dream into a manifest reality. The gospel is the good news of the freedom of the dream of God erupting through the confines of our everyday world. It is the story of the dream of God taking on flesh and coming to life among us. It is the story of the One who fully embodied that dream. The gospel is also about us — our calling, our redemption, our freedom, and our empowerment. It is the dangerous story about our being rescued from forces of domination that lead to death and destruction and awakened to the power of the Spirit of life that calls us forth to join in making the world new. Even so, the gospel is the story of the calling of the church. It is the story of how we have been called and empowered together by the Holy Spirit of God to embody — in our very bodies — that same dream, the cry at the core of the Creation, the yearning at the heart of the universe. The church exists, you see, to embody the dream of God.

The Dreams of Tremont

I was reading the other day in a history book about the ancient peoples who used to inhabit this land, long forgotten. They were mound builders, long before the Erie were here. I look at the mounds and try to learn about how their communities lived, and I ask myself: “I wonder what their dreams were for this land.”

I read about the Six Nations, the Greenville Treaty of 1795. This is one of those episodes of human history where we get to see how power works, how dreams become realities, and how they can completely annihilate communities rather than empower and heal them. I think about all of the people whose families were represented by those who signed the treaty and had to journey to find new places to call home. By that time, these communities had spent almost two hundred years fighting to survive. Any dreams they might have had for this land were stolen from them by men like Moses Cleaveland. They were dreamers whose dreams for survival inspire us on our ways forward.

I read about the Connecticut Land Company, which had 36 founders and 7 directors. What about their dreams? I read about how Moses Cleaveland was among them, and how he was sent with a team to map and survey the property they would now have access to. Still, they had to negotiate with the Massasagoes tribe. Moses Cleaveland wrote in his journal that they were beggars and that they asked for more whiskey. There were reports from people who had spent a significant amount of time with them that said they had 30 cabins that were nice, clean, and “unusually comfortable.” So Moses Cleaveland “negotiated” and surveyed the land, and drew these series of boxes like a first grader with ruler and pencil in hand. What were his dreams for this land?

I read about how the “treaties opened the floodgates” for settlers. In 1832, when the Ohio & Erie Canal was finished, Tremont was a part of Brooklyn Township. Settlers began coming in. Pilgrim UCC down the street, as you know, is the oldest church in the area, founded in 1859. German immigrants began settling here, many by way of Pennsylvania. In 1867, a German Evangelical congregation was founded. What were their dreams for this place?

The Gospel and the Dream of God

We all have dreams for the spaces we inhabit. As the Minister of Faith in Action for our Association, I’m interested in the role our understanding of the gospel plays in the dreams we have about the spaces we inhabit. I believe our scripture passage this morning calls us to focus on this—the gospel and the dreams we have for our community. The call, this morning, is to see our Sabbath practices as times together to begin making that dream a reality. The Sabbath is a way of life, lived in accordance with the dream of God for the wholeness of the world.

Our passage this morning is part of the Travel Narrative. One thing that makes Luke special as a gospel is the journey. Luke has two volumes: Luke and Acts. Luke is the story of Jesus’ journey to Jerusalem. Acts is about Paul’s journey to Rome. In this central part of Luke, known as the Lucan Travel Narrative, Jesus has set his face to Jerusalem. Jesus “set his face” — prosopon — to go to Jerusalem. Jerusalem, see, was meant to be the city that embodied the dream of God. Jerusalem was supposed to be a thin place, a place where heaven was just within reach. It was supposed to be the place to find God, to come into connection with the force that brought Creation into being. It was in Jerusalem where broken souls were supposed to find healing. Jerusalem was supposed to be the birthplace for the dream of God.

The Lucan Travel Narrative tells how Jesus set his face toward Jerusalem — traveling the countryside, preaching, teaching, and healing. In the words of the historian of early Christianity, John Dominic Crossan, Jesus was working as an “alternative boundary keeper.” He went to those who had been disgraced and discarded and restored them to healing and wholeness in the context of a community of trust, friendship, and solidarity. Jesus taught that the poor, rejected, displaced and seemingly powerless were the beloved children of God. Jesus taught them that they had been empowered to bring about a whole new world. Jesus proclaimed to them the wildly radical notion that the dream of God — the Beloved Community — was breaking free into the world, into the here and now, and they were all invited to be a part of it.

Here I think of the wisdom of Alyssa Battistoni when she wrote about what organizers do. “Your job as an organizer was to find out what it was that people wanted to be different in their lives, and then to persuade people that it mattered whether they decided to do something about it. This is not the same thing as persuading people that the thing itself matters: they usually know it does. The task is to persuade people that they matter: they know they usually don’t.”

So we have the story of this movement of folks — suffering, everyday people — journeying throughout first century Palestine, through the villages of Judea, following Jesus, who had set his face toward Jerusalem, the city that was the central focus of the saga of the dream of God. Jesus sends out 72 of his followers: “The harvest is plentiful but the workers are few” (Lk 10:2). Jesus tells them that there are multitudes out there, broken and in need of healing, an uncountable number of folks waiting to hear the truth of the love of God, to participate in this in-breaking of the dream of God for the healing of the world.

He sent them out, into homes. Jesus said, “If they hear the stories of the broken finding healing and belonging in a community that accepts them as they are, and they listen, they have listened to me.” If they don’t, just wipe the dust off your feet and move on.

I would love to spend this morning walking with you through the whole story. I’d love to tell you about how Jesus told an academic that there is no room in the dream of God for people to be left for dead in ditches. We would walk you through the story of how Jesus invited a family to give up all of the things they were preoccupied with and to invest their lives into “the one thing that was needed,” their participation in the unfolding of the dream of God.

Today in our reading, we get a glimpse into what it was like to be in a teaching moment with Jesus. A woman came and asked to be healed. Jesus healed her. And that turned into a debate. You have probably heard that this was a debate about whether Jesus was “breaking the law” on the Sabbath. Instead, it’s opens the window for conversations about one of the fundamental questions about the nature of religious practices. The problem is, we missed the first part of the story. We missed the context. Jesus was teaching about repentance. He had only just been having a conversation with them about the killing of rebellious Galileans — Jesus was from Galilee and his followers had Zealots in their midst. “Were they tortured by Pilot because they were sin people?” Of course not, he would say. But he told them that the same thing would happen to them if they did not change. He talked about a Siloam that had fallen, and how 18 people had died when a tower at Siloam fell. That did not happen because they were sinful people. And the same destruction was coming upon them, unless they did something to change things. So, they were being called to care for their communities. To become fruit bearing communities by learning to care for each other, or expect to suffer the consequences. It was the same message he had been preaching about all along.

It is at this point that a lady walks in and asks for healing. Some of them didn’t get it. They wanted to criticize him for it. This is a perfect illustration of what John Dominic Crossan was talking about in calling Jesus an alternative boundary keeper. They had placed a boundary around the Sabbath. Instead of a practice aimed at healing, the Sabbath had become a tool in support of oppression. It was not a day of festivity and joy. It was not a day for celebrating the birthing of the dream of God. It was not a day for mutual learning and growing and healing together. The Sabbath, Jesus then began to teach them, is the name given to the weekly celebration of the God’s dream for the world’s wholeness. What is the sabbath for?

It is for celebration. It is for community. It is for freedom.

It is for life. It is for justice. It is for healing.

The question I believe we are being asked this morning to consider is this: What would it look like for Zion UCC to live as an embodiment of the dream of God? Or, asked differently — What does God’s dream for the wholeness of Creation look like here in Tremont? What role does Zion UCC play in that?

The Invitation for the People of Zion

This morning, I am coming to invite you to be part of a movement. The Living Water Association has called me for the sole expressed purpose of helping our churches get really good at caring for our communities. We are made up of 150 congregations. God is calling all 150 of our congregations to “journey together” to discover what the dream of God looks like for the northeastern Ohio. I’m inviting you to journey with us to imagine what the dream of God looks like for Tremont, for the whole city of Cleveland, for the entire Rust Belt. When we look out at the world around us, here in 2019, what do we dream for our community? What do we believe God cares about here?

Cuyahoga county has a total of 534,355 households, 9,161 of those households live in this part of Cleveland, within the 44113 zip code tabulation area. (That includes Ohio City and the Warehouse District.) According to a United Way report, 47% of the households in our area struggle to make ends meet every month. That is 251,146 in Cuyahoga County who struggle from day-to-day to decide whether to pay the rent, the heat bill, or the groceries, or their doctor bills, because they absolutely cannot miss a payment on their childcare, because no matter what tragedy comes, they cannot miss a day at work. Two-hundred fifty one thousand. That number means it likely includes some of you. The question I’m asking is about God’s dream for our community, and whether the gospel has something to say about our situation.

I pray this morning that we hear Jesus’ invitation. I pray we hear the invitation to rediscover the Sabbath as a day for celebrating, for dreaming, for working to embody the dream of God. The gospel is the mighty and dangerous story about the dream of God coming to pass among us. God is calling us to center our lives, to rediscover the Sabbath as a way of life centered around this dream of God for the worlds wholeness. On behalf of those of us who are desperate to see the dream of God become a reality in our communities, Zion would has been invited to be a part of it. I pray that you will hear that invitation and that you are able to participate in the dream of God as it is breaking forth in Tremont, all over Northeast Ohio, and to the world.

—Amen.