The Revolutionary Politics of Love

When the Pharisees heard that he had silenced the Sadducees, they gathered together, and one of them, a lawyer, asked him a question to test him. “Teacher, which commandment in the law is the greatest?” He said to him, “’You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.”

For those of us who realize the political import of the story of Jesus, this section of Matthew (chs 19-22) is quite resourceful. Jesus has come into Jerusalem like a king (21:1-11), cleansed the temple (21:12-13), and had his authority challenged by the chief priests and the elders (21:23-27). He responds by telling them that the tax collectors and the prostitutes will make it into God's kingdom before they do (21:31). Alluding to a well-known passage about a vineyard from Isaiah 5, Jesus calls the Jerusalem elite wicked tenants (22:33-46) because they have been more preoccupied with propping themselves up than caring for God's people. He then uses a story of a wedding banquet to describe these religious elite as bullies who had originally been invited but "did not deserve to come" (22:1-14).

Then comes the often quoted passage (22:15-22) that portrays the competition between Jesus and the Roman Emperor. "Should we pay taxes to Caesar, or not?" The Pharisees have gone and teamed up with some unlikely allies, the Herodians, to challenge Jesus about his position when it comes to paying the poll tax. It is important to note here that the divisions within the first-century Jewish community are varied responses to the rule of the Romans. (See John Howard Yoder, The Original Revolution, pp. 18-27). The Pharisaic option emphasized the importance of Torah obedience and ritual purity as the means to restoring Israel to its original glory. The Sadducees and the Herodians saw that the best way to respond to Roman power was through collaboration rather than opposition. The Essenes responded by withdrawing. The Zealots, mostly in agreement with the Pharisees, responded by initiating armed rebellion, declaring that "God is to be their only Ruler and Lord" (Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 18:1.6). This was deeply important when it came to the challenge brought to Jesus about paying taxes.

Around the time of Jesus' birth, a census was issued by the Roman government (the Census of Quarinius), and for the first time, Roman soldiers came in to enforce a tax on the people in the Judean region (cf. Luke 2:1-7). In response, a Galilean named Judas rose up and initiated a revolt (Josephus, Jewish Wars II, 8). Even though they were quickly struck down by the Romans, the unrest lasted throughout the time of Jesus' ministry. When the temple in Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans in 70 C.E., there was a backlog of imperial taxes to pay, and a number of coins for "liberated" Jerusalem had been minted. (See Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man, p. 314.) Thus, the question as to whether or not to pay taxes was not just one among many issues; it represented the major political problem for the people during the time of Jesus' ministry. It was the question to Jesus: "Whose side are you on?"

Jesus' famous answer--"Give to Caesar what is Caesar's, and give to God what is God's"--was not his way of just shrugging off the question as if it was irrelevant. Instead, the notion of giving to God what belongs to God was deeply political. By asking his hearers whose image was on the coin, he was calling them to reconsider where they should expect to find God's image.

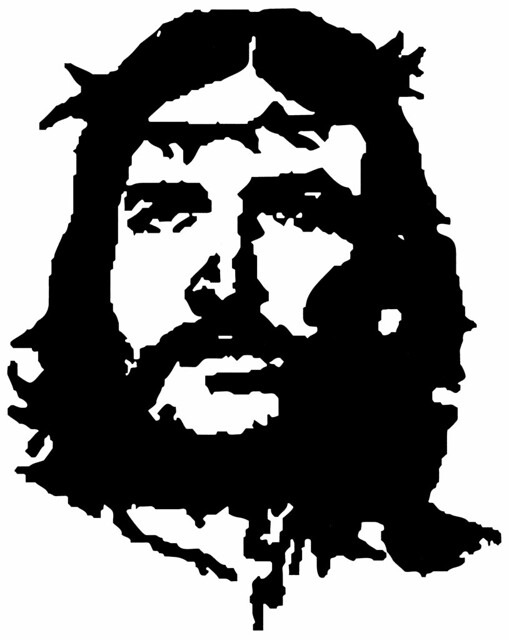

And here is where the important question about the Great Commandment comes in. Jesus' political response created a revolution. Like the Zealots, it was a direct affront to the politics of Rome. As the context here in Matthew makes clear, it was also an affront to the religious authorities. Jesus' answer was not a way of non-involvement, but of undivided loyalty to God. But unlike Judas of Galilee and the Zealots, this loyalty required a new vision, a revolution without swords.You might say that Jesus was a non-violent revolutionary, a Zealot pacifist.

As John Howard Yoder explained,

He did not agree that to use superior force or cunning to change society from the top down by changing its rulers, was the real need. What is wrong with the violent revolution according to Jesus is not that it changes too much but that it changes too little; the Zealot is the reflection of the tyrant whom he replaces by means of the tools of the tyrant. The Zealot resembles the tyrant whom he attacks in the moral claims he makes for himself and his cause...One of the clear differences between Jesus and the Zealots was His readiness to associate with the impure, the sinner, the publican, the Roman...

An order created by the sword is at the heart still not the new peoplehood Jesus announces. It still by its subordination of persons (who may be killed if they are on the wrong side) to causes (which must triumph because they are right), preserves unbroken the self-righteousness of the mighty and denies the servanthood which God has chosen in His tool to remake the world. (JH Yoder, The Original Revolution, pp. 23-24).

Jesus' response--to give to God what is God's--calls us to see that it was not the Roman soldiers, nor the religious elite, who were the real enemies. The real enemy was the sword, the abusive politics of the Romans, the abusive powers of the empire. This means that the command to "give to God what is God's" requires us to look again and remember that all of us have been made in God's image. Our neighbors and our enemies are the divine images of God.

So, when Jesus explains that the law and the prophets all hang on the commandments to love God and love our neighbors, he is inviting his hearers to see that those around them were created in God's image. Thus, we are challenged to re-evaluate our lives, our commitments, and our politics and orient them in ways that honor that divine image in others.

Giving to God what is God's, loving our neighbors as ourselves, is a peculiar kind of politics. It is God's tool to remake the world. It requires us to expect to find God's image in our neighbors--and even in our enemies. Nevertheless, knowing how to give to God what is God's, how to honor the divine image in others, is not a task we are very good at.

What does it look like to have an undivided heart, to give an unrestrained love to God, our neighbors, and even our enemies?

Here is one way of thinking about it that has had a great influence on me...

When I was in India, I was fascinated by the Hindu worship practices--called puja. They have images of their gods posted everywhere: near their front doors, in their shops, and even on the dashboards of their cars. In their chapels they have these little figures that portray their gods, all elaborately decorated--majestic and beautiful. As an act of worship, during their times of prayer, they place offerings of flowers (pushpanjali) and spices, and sometimes even coins, in front of the images of their gods.

What Hindu worship should remind us Christians is that we are called to see the image of our God in the faces of the people around us, people created by God in God's image. What if, out of devotion to our God, we were to present our offerings before those in whom we are expected to find the divine image? What if giving to God what is God's included rethinking how to respond to our enemies?

What if, instead of just merely refusing to participate in violence against our enemies, we also took this as a call to bless them by presenting our offerings to God before them--as if we really believed that in them was the presence of God's image?

Would this not explain why it is so important for us to love our neighbors? Would this not fully explain how Jesus' call to love was an alternative politics to the sword, to the abusive systems of power around us?

One thing is for sure, it would change the way we think about what worship looks like.

Here's a video that helps demonstrate what love looks like--that love is how we honor the divine image we find in others.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H2UI25sayXk[/embed]